Every society goes through the pages of reform and change. But the leaders of society, representing the status quo, strongly resist any movement for reform and change since it deprives them of their leadership. Any establishment has its own leaders who would do everything to resist change, either in the name of religion or in the name of age old traditions. Those who advocate change are denounced as heretics, unbeliever and innovators and violators of religious sanctity. The real issues involved are sought to be drowned in the sea of such accusations.

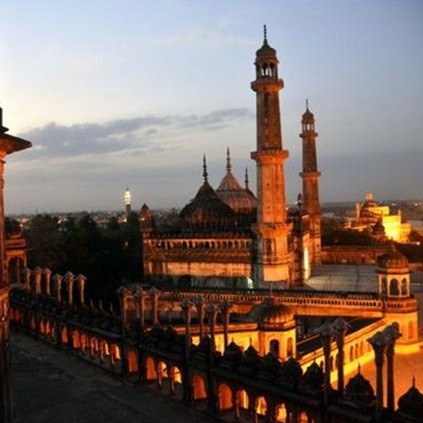

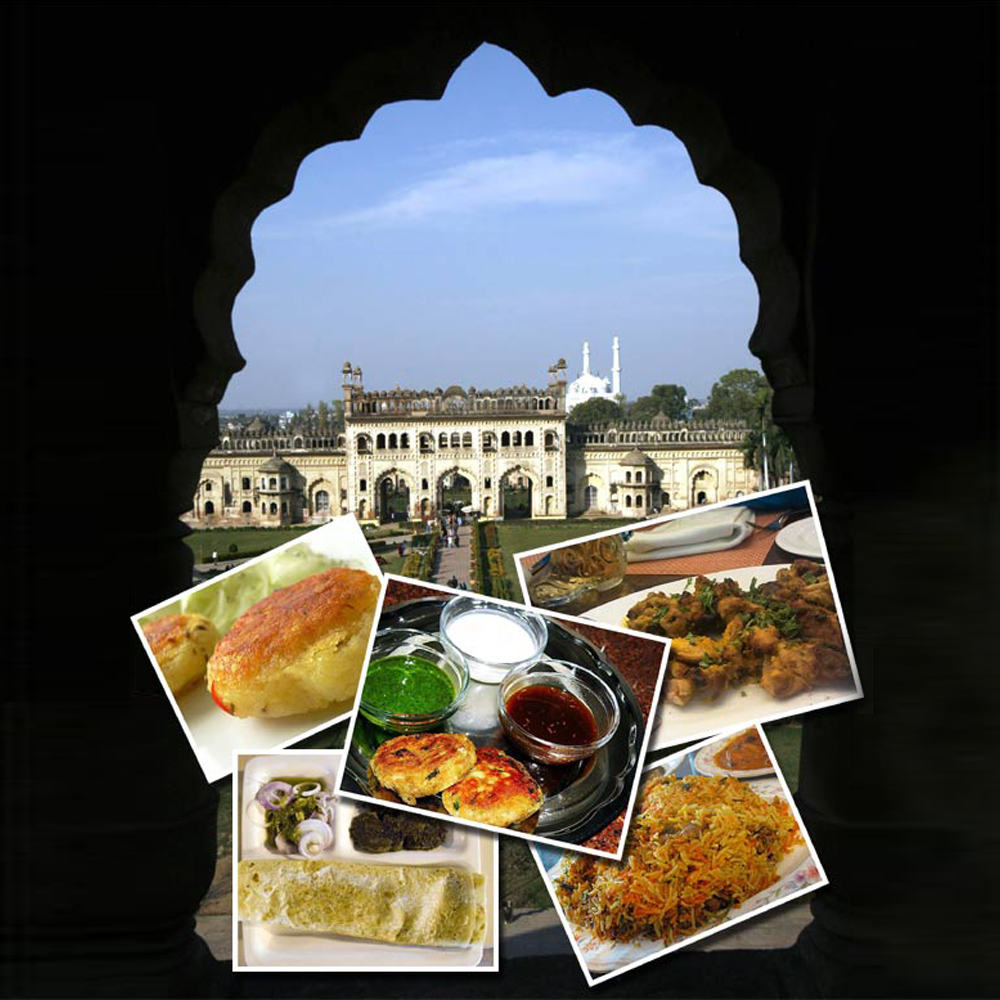

Like the great Indian publisher Munshi Nawal Kishore, who demonstrated the centrality of printing for colonized communities of a loss of sovereignty economic change and new social pressures? He has been called Caxton of India, William Caxton (c. 1422 – c. 1491) was an English merchant, diplomat, and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer was the first English retailer of printed books. Munshi Nawal Kishore was key knowledge brokers who drove forward intellectual debate, enabled critical reflection on the past and present and defined new horizons of cultural possibility. This great son of India opened a new era of the Indian printing press not only for Hindus but also for Muslims. Munshi Nawal Kishore started a printing press and unearthed rare books of Hindu and Islamic philosophers, Islamic literature, religion, in Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Hindi and Sanskrit and got them printed. The opening of his printing press in November 1858 marked a turning point in the history of printing in Lucknow (Now, Lucknow is the capital city of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India). As the first Indian to open a press in post – mutiny, Lucknow, he heralded a new era of the mass-produced book. Nawal Kishore reshaped local print culture and has been highlighted

Munshi Nawal Kishore was the second son of Munshi Jamuna Prasad Bhargava, a zamindar . There is a slight difference of opinion about Naval Kishore’s date of birth. Some scholars have mentioned that he was born in Bistoi, Aligarh district, in December 1836 while some others believe that he was born on January 3, 1836, in a village named Rerha in Mathura district. At the age of six, he was admitted in a local school (maktab) to learn Arabic and Persian. At the age on 10, he was admitted in Agra College, but he never completed his education there for an unknown reason. During this time, he developed his interest in journalistic writing, and issued a short-lived weekly paper Safeer-e-Agra. He briefly served as an assistant editor and editor of Koh-i-Noor, a magazine of Koh-i-Noor Press owned by Munshi Harsukh Roy.

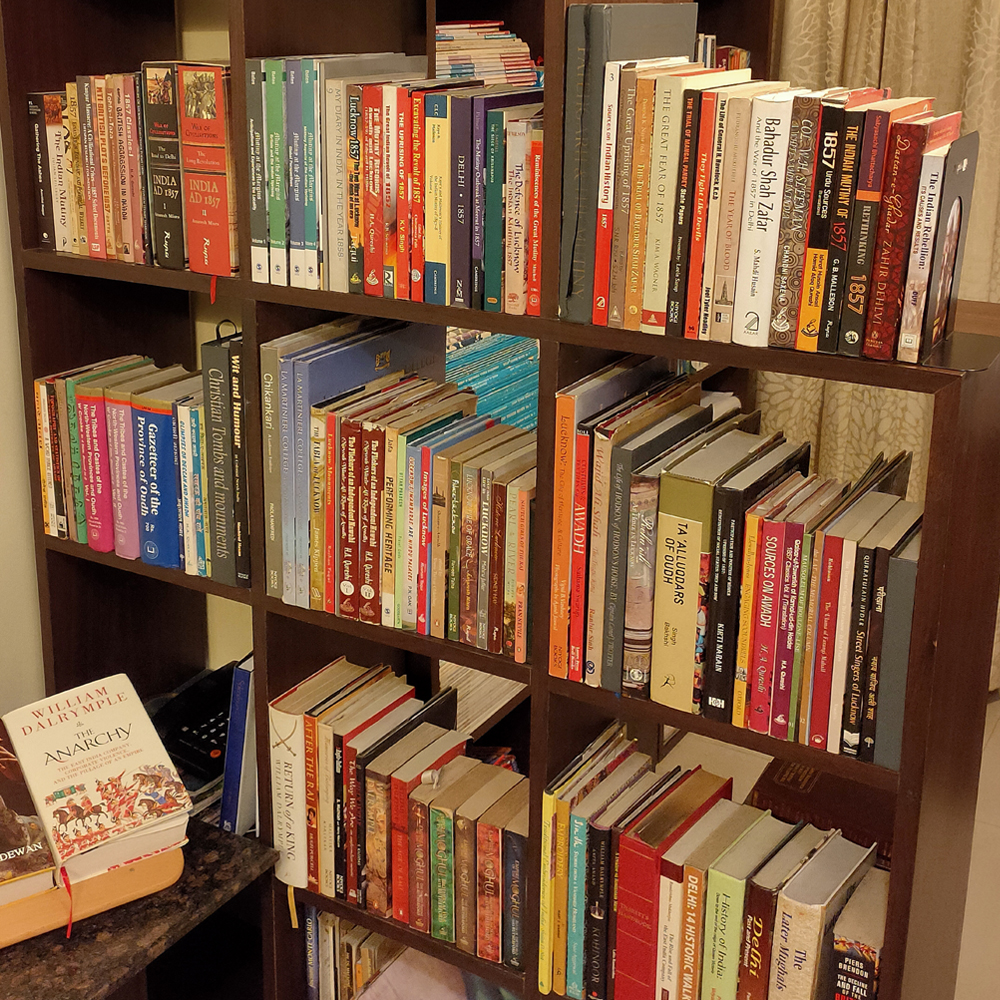

On 23 November 1858, he founded a printing press known as Munshi Nawal Kishor Press. From 1859, he started publishing weekly newspaper Avadh Akhbar, also known as Oudh Akhbar. The license of Printing press was given by British government. He started his journey with one handpress and few litho stones. Initially press was srtated at Wajirganj and then shifted to Golaganj and finally reached to Hazratganj. Munshi Nawal Kishore published more than 5000 books in Arabic, Bengali, Hindi, English, Marathi, Punjabi, Pashto, Persian, Sanskrit and Urdu during 1858–1885.

An Erudite scholor, educationalist and a nationalist, Munshi Ji was also a great social worker, Philanthropist and a pioneer industrialist. Munshi ji was made C.I.E. at a very young age and was given “Kaise-e-hind” medel in recognition of his public services and his services to the cause of education. But perhaps the greates tribute came to him from King Abdur Rahman of Afghanistan who in the presence of then Viceroy of India, Lord Dufferin and the prince of India at the Ludhiana Darbar in 1885, told Munshiji : I am thankful to the Lord that I have seen you. In India nothing has given me more pleasure than having you seen……

But all agree that he was truly a great benefactor of eastern learning. His ‘Naval Kishore Press’ was not merely a press or a publishing house. It was rather a great institution that was instrumental in preserving the endangered cultural heritage of 19th century India. Ghalib, while paying tributes to Naval Kishore Press, said “Divan of whosoever Naval Kishore published, his name and fame reached the sky.” Ameer Hasan Noorani in his book ‘Munshi Naval Kishore Haalaat aur Khidmaat’ (1982) wrote that “as soon as one mentions the words ‘Naval Kishore Press’, the pleasing and awe-inspiring thought of thousands of books fills one’s heart.” Aziz Ahmed, Urdu’s well-known fiction writer-turned-scholar once remarked “Had it not been for Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Munshi Naval Kishore after the failed 1857 War of Independence, the general awakening of India to a different environ and the preservation of our cultural heritage would not have been possible. … If Naval Kishore had not rediscovered our invaluable cultural treasure through printing and publishing, it would have been lost forever after the calamity of 1857. It would have been a kind of cultural loss repair to which would have not been possible.” In 1858, he reached Lucknow. He felt that the environment at Lucknow, once a jewel in the Indian crown and a centre of oriental learning, was conducive to his ambitious plans. Here he bought some litho hand presses and began business in a small rented house. He had but a small capital and could not afford any whimsical ideas so he began with printing some textbooks and some religious volumes as they, just like those days, would not take long to sell.

British patronage was one of the main factors accounting for the Nawal Kishore Press’s rapid growth and expansion. Without wanting to downplay Munshi Nawal Kishore’s own achievement as an entrepreneur, it is hardly overstating the case to say that colonial patronage significantly distinguished the history of the Nawal Kishore Press from that of other Indian publishers. The business relationship between the Nawal Kishore Press and the colonial authorities, along with the circumstances attending colonial patronage, should be analyzed in greater detail. The picture that emerges illustrates the complex transnational relations between Indian private entrepreneurship and state authority, depicting at once an intense and extremely successful business collaboration and a sustained dispute over market shares and profits, as well as agency and control in the publishing market.15 The patronage by individual British officials, however, also needs to be situated within the context of government policy towards the Indian-language press and print media in the wake of the 1857 uprising.

Viewed against this backdrop the Nawal Kishore Press’s collaboration with the colonial administration displays all the characteristics of a symbiotic relationship: at the time of setting up a business. Nawal Kishore relied heavily on British patronage in the various forms of license grant, technological and material support and printing contracts. The Avadh provincial authorities, on the other hand, had a vested interest in securing the collaboration of a loyal representative of the Indian language press in the politically sensitive post- Munity days. An editor- publisher of proven loyalty such as Nawal Kishore was an asset to be co-opted and duly instrumentalized in the process of reconsolidating power and counter- acting anti –colonial sentiment. At the pragmatic, political and ideological level, the establishment of the Nawal Kishore Press was a welcome opportunity for the new rulers

Soon the press was doing a roaring business and printing orders from government were pouring in. Naval Kishore was quick to switch over to bigger and better printing machines. His services for Islam are unprecedented. His unprejudiced disposition ensured that alongside Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavad-Gita, the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth as well are published. For the purpose he especially hired some Muslim scholars and workers. The Qur’ān, Ḥadīth and other religious publications for Muslims were well received and in fact satisfied the needs of a huge segment of the society

After that, Munshi Nawal Kishore printing press was gradually popularized throughout the Hindu–Muslim both communities in India. That time The Muslim were identified as the principal instigators of the rebellion in a feeble attempt at reigniting the lost glory of the Mughal Empire. After that, Muslims were debarred from government services and expenditure on their education was curbed. The Dehli based Anglo-Indian Press was no less impassioned in questioning the capacity of Muslims to be loyal to a non-Muslim conspiracy to set alight the torches of insurrection. 1857 proved to be cataclysmic for the Muslim community in India, which was adversely affected socially, culturally, financially, and also educationally. In that condition Munshi Nawal Kishore Press opened a new era for the Muslim community and especially, the Islamic literature was saved, preserved and put in the hands of the public by a famous Munshi Nawal Kishore Press.

The literatures of Islam are normally classified into several areas of study. The canonical literature, the interpretation of scripture and tradition, law, theology and philosophy, often, distinct gems are recognized in history and mysticism or spirituality. It is a huge task to select the most significant texts from each of these areas. The Islamic world contains a rich tradition of extraordinary literature that stretches back for centuries. Literature was the preeminent form of early Islam and it has retained its high status over the centuries. There are several reasons for this. One is that a solid foundation existed upon which to build Islamic literature. This foundation had been laid in Arabia, Islam’s homeland, long before the birth of the religion’s founder, the Prophet Muhammad. Arabs had developed a highly sophisticated oral literary tradition. As Islam spread eastward writers in India produced works not only in Arabic and Persian but also in Urdu language. Many Indian vernaculars contain almost exclusively Islamic literary subjects

India’s share in the development of Islamic literature at this time was especially large. In addition to the theological work written in the language of the Qur’ān, from the conquest of Sind in 711 right up to biographical literature in Arabic was also being written in the sub-continent. Persian taste predominated in the northwest of India, but in the southern provinces there were long standing commercial and cultural relationship with the Arabs and an inclination toward preserving these intact. Thus, lot of poetry in conventional Arabic style was written during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, mainly in the kingdom of Golconda. The main contribution of Muslim India to high literature was made in the Persian tongue. Persian had been the official language of the country for many centuries. The numerous annals and chronicles that were compiled during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as well as the court poetry, had been composed exclusively in this language even by Hindus. During the Mughal period, its importance was enhanced both by Akbar’s attempt to have the main works of classical Sanskrit literature translated into Persian and by the constant influx of poets from Iran who came seeking their fortune at the lavish tables of the Indian Muslim grandees. At this time what is known as the Indian style of Persian emerged. and after that Urdu.24 Hence the Muslim literature was preserved by the Indian Muslim rulers, but after that when the colonial period was established, Muslims preserved their tradition through publishers of the printing press. And Munshi Nawal Kishore Press was important in the preserving Islamic literature. It was not only the largest establishment of its kind in the entire sub-continent, but also the single most important institution in the mass production of low price printed books in Islamic literature.

All the name and fame did not deter Munshi Newel Kishore from fostering the political inspiration of his people. In 1885 he joined the rank of congress founding fathers and played his role in founding of Indian National Congress. His friends and admirer includes Allan Octavian Hume and Sir Surendra Nath Banerjee.

At the age of 59, Munshi Naval Kishore died all of a sudden. But the legacy that he left behind is simply unforgettable and cannot be squandered.