On the eve of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Lucknow, the capital of the Kingdom of Avadh, was indisputably the largest, most prosperous and most civilised pre-colonial city in India. Its spectacular skyline – with its domes and towers and gilded cupolas, palaces and pleasure gardens, ceremonial avenues and wide maidans – reminded travellers of Constantinople, Paris or even Venice. The city’s courtly Urdu diction and elaborate codes of etiquette were renowned as the most subtle and refined in the subcontinent; its dancers admired as the most accomplished; its cuisine famous as the most flamboyantly baroque. Moreover, at the heart of the city, lay Lucknow’s decadent and Bacchanalian court. Stories of its seven-hundred women harems and numberless nautch girls came to epitomise the fevered fantasies of whole generations of Orientalists; yet for once the fantasy seems to have been not far removed from the clearly swaggeringly sybaritic reality.

“But look at it now”, said Mushtaq gesturing sadly over the rooftops. “See how little is left…..”

We were standing on the roof of Mushtaq’s school in Aminabad, the oldest quarter of the city and the heart of old Lucknow. It was a cold, misty winter’s morning and around us, through the ground mist, rose the great swelling, gilded domes of the city’s remaining mosques and Imambaras. A flight of pigeons wheeled over the domes and came to rest in a grove of tamarind trees to one side; nearby a little boy flew a kite from the top of a small domed Mughal pavilion. It was a spectacular panorama, still one of the greatest skylines in all Islam; but even from our vantage point the signs of decay were unmistakable.

“See the grass growing on the domes?” said Mushtaq, pointing at the great triple dome of the magnificent Jama Masjid. “It hasn’t been whitewashed for thirty years. And at the base: look at the cracks! Today the skills are no longer there to mend these things: the expertise has gone. The Nawabs would import craftsmen from all over India and beyond: artisans from Tashkent and Samarkand, masons from Isfahan and Bukhara. They were paid fantastic sums, but now no one ever thinks to repair these buildings. They are just left to rot. This has all happened in my lifetime.”

A friend in Delhi had given me Mushtaq Naqvi’s name when he heard I was planning to visit Lucknow. Mushtaq, he said, was one of the last remnants of old Lucknow: a poet, teacher and writer who knew Lucknow intimately yet who – slightly to everyone’s surprise – had chosen never to leave the city of his birth, despite all that had happened to Lucknow since Independence. Talking with my friends, I soon learned that this qualification -“despite all that has happened to Lucknow ” – seemed to be suffixed to any statement about the place, as if it was a universally accepted fact that Lucknow’s period of greatness lay long in the past.

The city’s apogee, everyone agreed, was during the eighteenth century under the flamboyant Nawabs of Avadh (or Oudh) – a time when, according to one authority, the city resembled an Indian version of [pre-Revolutionary] “Teheran, Monte Carlo and Las Vegas, with just a touch of Glyndebourne for good measure”. Even after the catastrophe of the Mutiny, Lucknow had been reborn as one the great cities of the Raj.

It was Partition in 1947 that finally tore the city apart, its composite Hindu-Muslim culture irretrievably shattered in the unparalleled orgy of bloodletting that everywhere marked the division of India and Pakistan. By the end of the year, the city’s cultured Muslim aristocracy had emigrated en masse to Pakistan and the city found itself swamped instead with non-Muslim refugees from the Punjab. These regarded the remaining Muslims with the greatest suspicion- as dangerous fanatics and Pakistani fifth columnists- and they brought with them their own very different, aggressively commercial culture. What was left of the old Lucknow, with its courtly graces and refinement, quickly went into headlong decline. The roads stopped being sprinkled at sunset, the buildings ceased to receive their annual whitewash, the gardens decayed, and litter and dirt began to pile up unswept on the pavements.

Fifty years later, the city is today renowned not so much for its refinement as for the coarseness and corruption of its politicians, and the crass ineptitude of its officials. What had once been regarded as the most civilised city in India – a city whose manners and speech made other Indians feel like oafish rustics – is rapidly becoming notorious as one of the most hopelessly backward and violent, with a burgeoning mafia and a notoriously thuggish and corrupt police force.

“You must have seen some sad changes in that skyline,” I said to Mushtaq, as we turned to look eastwards over the monsoon-stained tower blocks which dwarfed and blotted out the eighteenth century panorama in the very centre of the city.

“In thirty years all sense of aesthetics have gone from this town,” he replied. “Once Lucknow was known as the Garden of India. There were palms and gardens and greenery everywhere. Now so much of it is eaten up by concrete, and the rest has become a slum. See that collapsing building over there?”

Mushtaq pointed to a ruin a short distance away. A few cusped arches and some broken pillars were all that was left of what had clearly once been a rather magnificent structure. But now shanty huts hemmed it in on three sides while on the fourth stood a fetid pool. At its side you could see a cow munching on a pile of chaff.

“It is difficult to imagine now,” said Mushtaq, “but when I was a boy that was one of the most beautiful havelis [courtyard houses] in Lucknow. At its centre was a magnificent shish mahal [mirror chamber]. The haveli covered that whole area where the huts are now and that pool was the tank in its middle: begums [aristocratic ladies] from all over Aminabad and Hussainabad would go there to swim. There were gardens all around. See that tangle of barbed wire? That used to be an orchard of sweet-smelling orange trees. Can you imagine?”

I looked at the scene again, trying to picture its former glory. It was very difficult.

“But the worst of it- how to put it in English?- is that the external decay of the city is really just a symbol of what is happening inside us: the inner rot.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Under the Nawabs Lucknow experienced a Renaissance that represented the last great flowering of Indo-Islamic genius. The Nawabs were such liberal and civilised figures: men like Wajd Ali Shah- author of one hundred books, a great poet and dancer. But the culture of Lucknow was not just limited to the elite: even the prostitutes could quote the great Persian poets; even the tonga drivers and the tradesmen in the bazaars spoke the most chaste Urdu and were famous across India for their exquisite manners…”

“But today?”

“Today the grave of our greatest poet, Mir, lies under a railway track. What is left of the culture he represented seems hopelessly vulnerable. After Partition nothing could ever be the same again. Those Muslims who were left were the second rung. They simply don’t have the skills or education to compete with the Punjabis, with their money and business instincts and garish, brightly-lit shops. Everything they have has crumbled so quickly: the owners of palaces and havelis have become the chowkidars [gate keepers]. If you saw any of the old begums today you would barely recognise them. They are shorn of all their glory, and their havelis are in a state of neglect. They were never brought up to work- they simply don’t know how to do it. As they never planned for the future, many are now in real poverty. In some cases their daughters have been forced into prostitution.”

“Literally?”

“Literally. I’ll tell you one incident that will bring tears to your eyes. A young girl I know- eighteen years old, from one of the royal families- was forced to take up this work. A rickshaw driver took her in chador to Clarkes Hotel for a rich Punjabi businessman to enjoy for 500 rupees. This man had been drinking whisky but when the girl unveiled herself, he was so struck by her beauty – by the majesty of her bearing – that he could not touch her. He paid her the money and told her to go.”

Mushtaq shook his head sadly: “So you see it’s not just the buildings: the human beings of this city are crumbling too. The history of the decline of this city is written on the bodies of its people. Look at the children roaming the streets, turning to crime. Great grandchildren of the Nawabs are pulling rickshaws. If you go deeply into this matter you would write a book with your tears.”

Mushtaq pointed at the flat roof of a half-ruined haveli: “See that house over there?” he said. “When I was a student there was a nobleman who lived there. He was from a minor Nawabi family. He lived alone, but everyday he would come to a chaikhana [teahouse] and gupshup [gossip]. He was a very proud man, very conscious of his noble birth, and he always wore an old fashioned angurka [long Muslim frockcoat]. But his properties were all burned down at Partition. He didn’t have a job and no one knew how he survived.

“Then one day he didn’t turn up at the chaikhana. The next day and the day after there was no sign of him either. Finally on the fourth day the neighbours began to smell a bad smell coming from his house. So they broke down the door and found him lying dead on a charpoy [cot]. There was no covering, no other furniture, no books, nothing. He had sold everything he had, except his one pair of clothes, but he was too proud to beg, or even to tell anyone of his problem. When they did a post mortem on him in the medical college they found he had died of starvation.

“Come,” said Mushtaq. “Let us go to the chowk: there I will tell you about this city, and what it once was.”

At the height of the Moghul Empire, said Mushtaq, Shah Jehan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, had ruled over a mighty Empire that stretched from the Hindu Kush in the North to great diamond mines of Golconda in the South. But during the eighteenth century, as the Moghul Empire fell apart, undermined by civil war and sacked by a succession of invaders from Persia and Afghanistan, India’s focus moved inexorably eastwards from Delhi to Lucknow. There the Nawabs maintained the fiction that they were merely the provincial governors of the Moghuls, while actually holding a degree of real power and wealth immeasurably greater than the succession of feeble late Moghul monarchs who came and went on the throne of Delhi.

Gradually, as the Moghul’s power of patronage waned ever smaller, there was a haemorrhage of poets and writers, architects and miniature painters away from Delhi to Lucknow, as the Nawabs collected around them the greatest minds of the day. They were men such as Mir, probably the greatest of all the Urdu poets, who at the age of 66 was forced to flee from his beloved Delhi in an effort to escape the now insupportable violence and instability of the Moghul capital.

The Nawabs were great builders, and in less than 50 years they succeeded in transforming the narrow lanes of a small mediaeval city to one of the great capitals of the Muslim world: “Not Rome, not Athens, not Constantinople, not any city I have ever seen appears to me so striking and beautiful as this,” wrote the British war correspondent William Russell in the middle of the Indian Mutiny. “The sun playing on the gilt domes and spires, the exceeding richness of the vegetation and forests and gardens remind one somewhat of the view of the Bois de Boulogne from the hill over St. Cloud… but for the thunder of the guns and the noise of the balls cleaving the air, how peaceful the scene would be!”

After 600 years of Islamic rule in India, what the Nawabs achieved at Lucknow represented the last great swansong of Indo-Islamic civilisation, a last burst of energy and inspiration before the onset of a twentieth century holding little for Indian Muslims except division, despair and decline.

Since I had arrived in the city I had spent a couple of bright, chilly winter days jolting around the old city on a rickshaw visiting a little of what was left. The architecture of the Nawabs has sometimes been seen as a decadent departure from the pure lines of the Great Moghul Golden Age, and there is some truth in this: there is nothing in Lucknow, for example, to compare to the chaste perfection of the Taj. Moreover, in the years leading up to the Mutiny, some of the buildings erected in Lucknow did indeed sink into a kind of florid, camp voluptuousness which seem to have accurately reflected the mores of a Lucknow whoring and dancing its way to extinction. To this day a curtain covers the entrance to the picture gallery in Lucknow after a prim British memsahib fainted on seeing the flirtatiously bared nipple of the last Nawab, Wajd Ali Shah, prominently displayed in a portrait of the period. The same feeling of over-ripe decadence is conveyed in Late Nawabi poetry, which is some of the most unblushingly fleshy and sensual ever written by Muslim poets:

I am a lover of breasts

Like pomegranates;

Plant then no other trees

On my grave but these.(Nasikh)

Confronted with such verses, Mir expressed his view that most Lucknavi poets could not write verse and would be better advised to “stick to kissing and slavering”. He may well have thought the same of Late Nawabi architecture with its similarly unrestrained piling on of effects. For by the end Lucknow’s builders had developed a uniquely blowsy Avadhi rococo whose forms and decorative strategies seem to have borrowed more frequently from the ballrooms and fairgrounds of Europe than from the shrines and fortresses of Babur and Tamburlaine. There was no question of sobriety or restraint: even in monuments built to house the dead, every inch of the interior was covered with a jungle of brightly coloured plaster work intertwining promiscuously with gaudy curlicues of feathery stucco.

Nevertheless the best of the buildings in Lucknow- those that date from the late eighteenth century- are evidence of a remarkable Silver Age which in sheer exuberance has no equal in India. The Great Imambara complex was built by Asaf ud-Daula for Shi’ite religious discourses in 1784. One of the largest vaulted halls in the world, it was built to create employment during a famine. Here there is none of the camp doodling that would be seen on later monuments. Instead the imambara is a vast and thoroughly monumental building: long, echoing arcades of cusped arches give way to great gilded onion-domes and rippling lines of pepperpot semi-domes; at the corners soaring minarets rise to solid well-designed chattris. The whole composition exudes a bold, reckless and extravagant self-confidence. Lucknow was consciously aiming to surpass the glories of Late Moghul Delhi and the Great Imambara shows it could do so with dashing panache.

Driving today through the melancholic streets of modern Lucknow, these massive buildings dating from the days of the Nawabs rear out of the surrounding anarchy like monuments from some lost civilisation, seemingly as disconnected from the present as the pyramids are to modern Egypt. At times it seems almost impossible to believe that they date from less than two hundred years ago, and that at that period Lucknow was famed as one of the richest kingdoms in Asia. For today the city is as shabby and impoverished as anywhere in India. Waves of squabbling cycle-rickshaw drivers pass down the potholed roads, bumping in and out of the puddles. Rubbish lies uncollected by the roadside, with dogs competing with rats to snuffle in the piles of street-side garbage. Beside them, lines of impoverished street vendors squat on dirty rush mats, displaying their tawdry collections of cheap plastic keyrings and fake Rolex watches. There is no grass in the parks and no flowers in the beds; barbed wire hangs limply around what were once beautiful Moghul gardens alive with the sound of parakeets and peacocks. Above the crumbling ruins of the old city of the Nawabs rise the charmless Monsoon-stained, smoke-blackened concrete blocks erected since Independence, and now, like the ruins, showing signs of imminent collapse, with deep fissures running up their sides.

The contrast between the magnificent follies of the Nawabs and the decayed, impoverished post-colonial intrusions which stand among them is almost unbearably painful: everywhere, it seems, there has been a universal drop in standards and expectations.

Yet even at the time the great buildings of Nawabi Lucknow were being erected, the Kingdom of Avadh was acutely conscious that it was living on borrowed time. For before the Nawabs had even established their capital at Lucknow, their armies had already been defeated in battle by the East India Company, and over the course of the early nineteenth century the Company ate like a cancer into the territories of Avadh: in less than 50 years the British annexed more than half the Kingdom. But the Nawabs remained surprisingly well disposed towards Europeans, and delighted in the trinkets and amusements Europeans could provide for their court: jugglers, portrait painters, watch menders, piano tuners and even fashionable London barbers were all welcomed to Lucknow and well paid for their services.

If the Nawab sometimes amazed foreign visitors by appearing dressed as a British admiral or even as a clergyman of the Church of England, then the Europeans of Lucknow often returned the compliment. Miniature after miniature from late eighteenth century Lucknow show Europeans of the period dressed in long white Avadhi gowns, lying back on carpets, hubble-bubbles in their mouths, as they watch their nautch girls dance before them. Even those who never gave up European dress seem to have taken on the mores of Nawabi society: Major General Claude Martin, for example, kept a harem which included his favourite wife Boulone as well as her three sisters. Nor was this sexual curiosity just one way: at least two British memsahibs were recruited to join the Avadi harem, and a mosque survives which was built by the Nawab for one of them, a Miss Walters.

Intellectually too, there seems to have been a surprising degree of intercourse between Europeans and the people of Lucknow. The greatest collection of Oriental Manuscripts in Britain – now the core of the India Office Collection – was formed by Richard Johnson while he was the Deputy to the British Resident in Lucknow. During his years in Avadh he mixed on equal terms with the poets, scholars and calligraphers of Lucknow, discussing Sanskrit and Persian literature, and forming long lasting friendships with many of them. One of these scholars, Mir Qamar ud-Din Minnat, dedicated his diwan to Johnson, later following his friend to Calcutta where Warren Hastings bestowed on him the title ‘King of Poets’.

Much of the surviving architecture of the city reflects this unique moment of Indo-European intermingling. Constantia, Claude Martin’s great palace-mausoleum, now the La Martiniere school, is perhaps the most gloriously hybrid building in India, part Nawabi fantasy and part Gothic colonial barracks. Just as Martin himself combined the lifestyle of a Muslim prince with the interests of a renaissance man- writing Persian couplets and maintaining an observatory, experimenting with map making and botany, hot air balloons and even bladder surgery – so his mausoleum mixes Georgian colonnades with the loopholes and turrets of a mediaeval castle; Palladian arcades rise to Mughal copulas; inside brightly coloured Nawabi plasterwork enclose Wedgwood plaques of classical European Gods and Goddesses.

Yet while Martin designed Constantia to be the most magnificent European funerary monument in India, the East India Company’s answer to the Taj Mahal, it was also intended to be defensible. The eighteenth century was an anarchic and violent time in India, and during an uprising in the 1770’s, Martin once had to defend his residence with a pair of cannon filled with grape shot. It was a lesson he never forgot, and he built Constantia to be his last redoubt in case of danger. Lines of cannon crowned the facade, and thick iron doors sealed off the narrow spiral staircases which connected the different ‘bomb-proof’ floors. Moreover on the facade Martin erected two colossal East India Company lions which were designed to hold flaming torches in their mouths. The sight of these illuminated beasts, belching out fire and smoke on a dark night was intended to terrify would-be intruders.

In its wilful extravagance and sheer strangeness, Constantia embodies like no other building the opulence, restlessness, and open mindedness of a city which lay on the faultline between East and West, the old world of the Nawabs and the new world of the Raj. To this day the whole extraordinary creation stands quite intact, still enclosed in acres of its own parkland. As you approach on your rickshaw you pass along a superb avenue of poplar and tamarind, eucalyptus and casuarina, at the end of which you pass the perfect domed Mughal tomb which Martin built for his beloved Boulone. As he rather touchingly wrote in his will: “she choosed never to quit me. She persisted that she would live with me, and since we lived together we never had a word of bad humour one against another.”

Nearby Constantia, a short rickshaw ride over the railway crossing, I stumbled across another smaller but equally remarkable building from the same period. It turned out to be the ruins of one of the Nawabs most lovely pleasure palaces, named Dilkusha or Heart’s Delight. Yet despite this very Persian name, Dilkusha was in fact closely modelled on one of the great English country houses, Seaton Delavel – but with four gloriously ornate octagonal minarets added to the otherwise austere Palladian design. The whole episode was an extraordinary moment of Indo-European fusion- a moment pregnant with unfulfilled possibilities, and one which is often forgotten in the light of Lucknow’s subsequent history.

For this process of mutual enrichening did not last. As the nineteenth century progressed, the British became more and more demanding in their exactions on the Nawabs, and more and more assured of their own superiority; they learned to scoff at the buildings and traditions of Lucknow, and became increasingly convinced that they had nothing to learn from ‘native’ culture. Relations between the Nawabs and the British gradually became chilly: it was as if the high-spirited tolerance of courtly Lucknow was a direct challenge to the increasingly self-righteous spirit of evangelical Calcutta. In 1857, a year after the British forcibly deposed the last Nawab, Lucknow struck back, besieging the British in their fortified residency.

In the event, after nearly two years of siege and desperate hand to hand fighting in the streets of Lucknow, the British defeated the Mutineers and wreaked their revenge on the conquered city. Vast areas of the city of the Nawabs were bulldozed, and for half a century the administration moved to Allahabad. Every site connected to the Mutiny was lovingly preserved by the British- the pockmarked ruins of the besieged Residency, the tombs of the British leaders who fell in the seige, every point in the town where the relieving forces were ambushed or driven back- turning much of the city into a vast open air Imperial War Memorial, thickly littered with a carapace of cemeteries and spiked canons, obelisks and Rolls of Honour. But shorn of its court and administrative status, preserved only for the curiosity of British visitors, Lucknow gradually became the melancholic backwater it is today.

“Yet even in my childhood something of Lucknow’s old graces survived,” said Mushtaq. “I’ll show you what I mean.”

We walked together through the chowk, the narrow, latticed bazaar-labyrinth which was once the centre of Lucknow’s cultural life. Above us, elaborately carved wooden balconies backed onto latticed windows. Figures flitted behind the wooden grilles. Every so often we would pass the arched and pedimented gateway of a grand haveli: the gateway still stood magnificently, but as often as not the old mansion to which it led had been turned into a godown or warehouse. A bird’s nest of electricity wires were strung down the side of the chowk, many of which had been brutally punched through the walls and arcades of the old mansions.

Below the latticed living quarters were a wonderful collection of tiny box-like shops, all arranged in groups by trade: a line of shops selling home-made fireworks would be followed by another line piled high with mountains of guavas or marigold garlands; a group of ear cleaners- whose life revolved around the patient removal of pieces of wax from the inner ear- would be followed by a confraternity of silver beaters who made their living from hammering silver into sheets so fine they could be applied to sticky Lucknavi sweets.

“When I was a boy, before Partition, I came here with my brother,” said Mushtaq. “In those days the chowk was still full of perfume from the scent shops. They had different scents for different seasons: khas for the hot season, bhela for the monsoon and henna for the cold. Everywhere there were stalls full of flowers: people brought them in from gardens and the countryside roundabout. The bazaar was famous for having the best food, the best kebabs and the best women in North India.”

“The best women?” Looking around all I could see now was the occasional black beehive flitting past in full chador.

“Ah,” said Mushtaq, “you see in those days the last courtesans were still here.”

“Prostitutes?”

“Not prostitutes in the western sense, although they could fulfil that function.”

“So what was it that distinguished them from prostitutes?” I asked.

“In many ways the courtesans were the guardians of the culture,” replied Mushtaq. “Apart from anything else they preserved Indian classical music from corruption for centuries. They were known as tawwaif, and they were the incarnation of good manners. The young men would be sent to them to learn how to behave and deport themselves: how to roll or accept a paan, how to say thank you, how to salaam, how to stand up, how to leave a room – as well as the facts of life.

“On the terraces of upper-storey chambers of the tawwaif, the young men would come to recite their verses and ghazals. Water would be sprinkled on the ground to cool it, then carpets would be laid out and covered with white sheets. Hookahs and candles would be arranged around the guests, along with surahis, fresh from the potters, exuding the monsoon scent of rain falling on parched earth. Only then would the recitations begin. In those days anyone who even remotely aspired to being called cultured had to take a teacher and to learn how to compose poetry.”

We pulled ourselves onto the steps of a kebab shop to make way for a herd of water buffaloes which were being driven down the narrow alley to the market at the far end. From inside came the delicious smell of grilled meat and spices.

“Most of all the tawwaifs would teach young men how to speak perfect Urdu. You see in Lucknow language was not just a tool of communication: it was a projection of the culture- very florid and subtle. But now the language has changed. Compared to Urdu, Punjabi is a very coarse language: when you listen to two Punjabis talking it sounds as if they are fighting. But because of the number of Punjabis who have come to live here the old refined Urdu of Lucknow is now hardly spoken. Few are left who can understand it- fewer still who speak it.”

“Did you ever meet one of these tawwaif?”

“Yes,” said Mushtaq. “My brother used to keep a mistress here in the chowk and on one occasion he brought me along too. I’ll never forget her: although she was a poor woman, she was very beautiful- full of grace and good manners. She was wearing her full make-up and was covered in jewellery which sparked in the light of the oil lamps. She looked like a princess to me- but I was hardly twelve, and by the time I was old enough to possess a tawwaif, they had gone. That whole culture with its the poetic mehfils and mushairas (levees and poetic symposia) went with them.”

“So is there nothing left?” I asked. “Is there no one who can still recite the great poets of Lucknow? Who remembers the old stories?”

“Well there is one man,” said Mushtaq. “You should talk to Suleiman, the Rajah of Mahmudabad. He is a remarkable man.”

The longer I lingered in Lucknow, the more I heard about Suleiman Mahmudabad. Whenever I raised the subject of survivors from the old world of courtly Lucknow, his name always cropped up sooner or later in the conversation. People in Lucknow were clearly proud of him and regarded him as a sort of repository of whatever wisdom and culture had been salvaged from the wreck of their city.

I finally met the man a week later at the house of a Lucknavi friend. Farid Faridi’s guests were gathered around a small sitting room sipping imported whisky and worrying about the latest enormities committed by Lucknow’s politicians. A month before, in front of Doordashan television cameras, the M.L.A’s in State Assembly had attacked each other in the debating chamber with microphone stands, desks and broken bottles. This led to heavy casualties, particularly among the high caste B.J.P politicians who had come to the Assembly building marginally less well armed than their low-caste rivals: around thirty had ended up in hospital with severe injuries, and there was now much talk about possible revenge attacks.

“Power has passed from the educated to the illiterate,” said one guest. “Our last chief minister was a village wrestling champion. Can you imagine?”

“All our politicians are thugs and criminals now,” said my neighbour. “The police are so supine and spineless they do nothing to stop them taking over the state.”

“We feel so helpless in this situation,” said Faridi. “The world we knew is collapsing and there is nothing we can do.”

“All we can do is to sit in our drawing rooms and watch these criminals plunder our country,” said my neighbour.

“The police used to chase them,” agreed the first guest. “But now they spend their time guarding them.”

Mahmudabad arrived late but was greeted with great deference by our host who addressed him throughout as ‘Rajah Sahib’. He was a slight man, but was beautifully turned out in traditional Avadhi evening dress of a long silk sherwani over a pair of tight white cotton pyjamas. I had already been told much about his achievements – how he was as fluent in Urdu, Arabic and Persian as he was in French and English, how he had studied post-graduate astrophysics at Cambridge, how he had been a successful Congress M.L.A under Rajiv Gandhi – but nothing prepared me for the anxious, fidgety polymath who effortlessly dominated the conversation from the moment he stepped into the room.

Towards midnight, as he was leaving, Mahmudabad asked whether I was busy the following day. If not, he said, I was welcome to accompany him to the qila, his ancestral fort in the country outside Lucknow. He would be leaving at 11am; if I could get to him by then I could come along and keep him company on the journey.

Suleiman’s Lucknow pied a terre, I discovered the following morning, turned out be the one surviving wing of the Kaiserbagh, the last great palace of the Nawabs. Before its partial destruction during the Mutiny, the Kaiserbagh had been larger than the Tuileries and the Louvre combined; but what remained more closely resembled some crumbling Sicilian palazzo, all flaking yellow plasterwork and benign baroque neglect. An ancient wheel-less Austin 8 rusted in the palace’s porte cochere, beside which squatted a group of elderly retainers all dressed in matching white homespun.

Suleiman was in his study, attending to a group of petitioners who had come to ask favours. It was an hour before he could free himself and call for the driver to come around with the car. Soon we had left the straggling outskirts of Lucknow behind us and were heading on a raised embankment through long straight avenues of poplars. On either side spread yellow fields of mustard, broken only by clumps of palm and the occasional pool full of leathery water buffaloes. As we drove Suleiman talked about his childhood, much of which, it emerged, had been spent in exile in the Middle East.

“My father,” he said, “was a great friend of Jinnah and an early supporter of his Muslim League. In fact he provided so much of the finance that he was made treasurer. But despite his admiration for Jinnah he never really seemed to understand what Partition would entail. The day before the formal split, in the midst of the bloodshed, he quietly left the country and set off via Iran for Kerbala [the Shia’s holiest shrine]. From there we went to Beirut. It was ten years before he took up Pakistani citizenship, and even then he spent most of his time in London.”

“So did he regret helping Jinnah?”

“He was too proud to admit it,” said Suleiman, “but I think yes. Certainly he was profoundly saddened by the bitterness of Partition and the part he had played in bringing it about. After that he never settled down or returned home. I think he realised how many people he had caused to lose their homes, and he chose to wander the face of the earth as a kind of self-imposed penance.”

Mahmudabad lay only thirty miles outside Lucknow but so bad were the roads that the journey took well over two hours. Eventually a pair of minarets reared out of the trees- a replica of the mosque at Kerbala built by Suleiman’s father- and beyond them, looking onto a small lake, towered the walls of the qila [fort] of Mahmudabad.

It was a vast structure, built in the same Lucknavi Indo-Palladian style I had seen at La Martiniere and Dilkusha. The outer wall was broken by a ceremonial gateway or naqqar khana [drum house] on which was emblazoned the fish symbol of the Kingdom of Avadh. Beyond rose the ramparts of a medieval fort onto which had been tucked an eighteenth century classical bow front; above, a series of balconies were surmounted by a ripple of Mughal chattris and copulas.

It was magnificent, yet the same neglect which had embraced so many of the buildings of Lucknow had also gripped the Mahmudabad qila. The grass had died on the lawn in front of the gateway, and the remaining flowers in the beds were twisted and desiccated; bushes sprouted from the fort’s roof. In previous generations the chamber at the top of the naqqar khana would have been full of musicians announcing the arrival of the Rajah with kettle drums and shehnai. It was empty now, of course, but there was certainly no shortage of servants to fill it. As we drove into the qila’s courtyard we saw a crowd of between twenty and 30 retainers massing to greet the rajah, all frantically bowing and salaaming; as Suleiman got out of the car the foremost ones dived to touch his feet.

I followed the rajah into the qila and up through the dark halls and narrow staircases of the fort; the troop of servants followed behind me. Dust lay thick underfoot, as if the qila was some lost castle in a child’s fairy tale. We passed through a splintered door into an old ballroom, empty, echoing and spacious. Once its floor had been sprung, but now many of the planks were missing and littered with pieces of plaster fallen from the ceiling. A torn family portrait of some bejewelled raja hung half in, half out of its frame. It looked as if no one had entered the room for at least a decade.

Finally, Suleiman threw back a door and led the way into what had once been the library. Cobwebs hung like sheets from the walls; the chintz was literally peeling off the arm chairs. Books were everywhere, great piles of 1920’s hardbacks, but you had to wipe the book with a handkerchief to read the spines and to uncover lines of classics – The Annals of Tacitus, The Works of Aristotle – nestling next to such long-forgotten titles as The Competition Wallah and The Races of the North West Provinces of India.

“This library was my ancestor’s window on the world,” said Suleiman, “but, like everything, it’s fast decaying, as you can see.”

I looked around. There were no carpets on the floors which, uncovered, had become stained and dirty. Above there were holes in the ceiling, with the wooden beams showing through the broken plaster like bones sticking out of wounded flesh. Suleiman was at the window now, pressing the shutters to try and open them; pushing too hard, he nearly succeeded in dislodging the whole window frame. Eventually the shutter gave way and hung open, precariously attached to the frame by its one remaining hinge.

A servant padded in and Suleiman ordered some cold drinks, asking when lunch would be ready. The servant looked flustered. It became apparent that the message had not reached them from Lucknow that we would be expecting lunch; probably the telephone lines were not working that day.

“It wasn’t always like this,” said Suleiman, slumping down in one of the chintzless armchairs underneath a single naked light bulb. “When the 1965 Indo-Pakistani war broke out, the qila was seized by the government as enemy property. My father had finally made the decision to take Pakistani citizenship in 1957, and although he had never really lived there, it was enough. Everything was locked up and the gates were sealed. My mother – who had never taken Pakistani citizenship – lived on the verandah for three or four months before the government agreed to allow her to have a room to sleep in. Even then it was two years before she was allowed access to a bathroom. She endured it all with great dignity. Until her death she carried on as if nothing had happened.”

At this point the bearer reappeared and announced that no cold drinks were available. Suleiman frowned and dismissed him, asking him to bring some water and to hurry up with the lunch.

“What was I saying?” he asked, distracted by the domestic chaos.

“About the sealing of the palace.”

“Ah yes. The Indian armed Constabulary lived here for two years. It wasn’t just neglect: the place was looted. There were two major thefts of silver- they said ten tons in all…”

“Tens tons? Of silver?”

“That’s what they say,” replied Suleiman dreamily. He looked at his watch. It was nearly three o’clock and his absent lunch was clearly on his mind. “Ten tons… though it’s probably exaggerated. Certainly everything valuable was taken: even the chairs were stripped of their silver backing.”

“Were the guards in league with the robbers?”

“The case is still going on. It’s directed against some poor character who got caught: no doubt one of the minnows who had no one to protect him.”

Suleiman walked over to the window and shouted some instructions in Urdu down to the servants in the courtyard below.

“I’ve asked them to bring some bottled water. I can’t drink the water here. My stomach- you’ve no idea the hell I’ve been through with it, the pain. I have to keep taking these terrible antibiotics. I’ve been to specialists, but they can’t do anything.”

Shortly afterwards the bearer reappeared. There was no bottled water, he said. And no, rajah sahib, the khana was not yet ready. He shuffled out backwards, mumbling apologies.

“What are these servants doing?” said Suleiman. “They can’t treat us like this.”

The rajah began to pace backwards and forwards through the ruination of his palace, stepping over the chunks of plaster on the floor.

“I get terrible bouts of gloom whenever I come here,” he said. “It makes me feel so tired – exhausted internally.”

He paused, trying to find the right words: “There is… so much that is about to collapse: its like trying to keep a dyke from bursting. Partly its because I don’t live here enough… But it preys on my mind wherever I am. I feel overwhelmed at even the thought of this place.

He paused again, raising his hands in a gesture of helplessness: “I simply can’t see any light at the end of any of the various tunnels. Each year I feel that it is less and less worth struggling for. Sometimes the urge just to escape becomes insupportable- just to leave it all behind, to take a donkey and some books and disappear.

“Come,” he said, suddenly taking my arm. “I can’t breathe. There’s no air in this room…”

The rajah led me up flight after flight of dark, narrow staircases until we reached the flat roof on the top of the fort. From beyond the moat, out over the plains, smoke and mist were rising from the early evening cooking fires, forming a flat layer at the level of the tree tops. To me it was a beautiful, peaceful Indian winter evening of the sort I had grown to love, but Suleiman seemed to see in it a vision of impending disaster. He was still tense and agitated, and the view did nothing to calm him down.

“You see,” he explained. “It’s not just the qila that depresses me. It’s what is happening to the people. There was so much that could have been done after Independence when they abolished the holdings of the zamindars [the big absentee landlords] who were strangling the countryside. But all that happened was the rise of these criminal politicians: they filled the vacuum and they are the role models today. Worse still theirs are the values – if you can call them values – to which people look up: corruption, deception, duplicity, crude, crass materialism. These are seen to be the avenues to success.

“The world that I knew has been completely corrupted and destroyed. I go into fits of depression when I see the filth and dirt of modern Lucknow and remember the flowers and trees of my youth. Even out here the rot has set in. Look at that monstrosity!”

Suleiman pointed to a thick spire of smoke rising from a sugar factory some distance away across the fields.

“Soft powder falls on the village all day from the pollution from that factory. It was erected illegally and in no other country would such a pollutant be tolerated. I spoke to the manager and he assured me action was imminent, but of course nothing ever happens.”

“Perhaps if you went back into politics you could have it closed down?” I suggested.

“Never again, ” said Suleiman. “After two terms in the Legislative Assembly I came on record saying I would leave the Congress Party if it continued to patronise criminals. The new breed of Indian politician has no ideas and no principles. In most cases they are just common criminals in it for what they can plunder. Before he died I went and saw Rajiv and told him what was happening. He was interested but he didn’t do anything. He was a good man, but weak: unsure of himself. He did nothing to stop the rot.”

“Do you really think things are that bad?” I asked

“There has been a decline in education, in health, in sanitation. There is a general air of misery and suffering in the air. It’s got much, much worse in the last fifteen years. Last week a few miles outside Lucknow robbers stopped the traffic and began robbing passers-by in broad daylight. Later, it turned out that the bandits were policemen.

“When I first joined the Legislative Assembly I was elected with an unprecedented majority. Perhaps you are right: perhaps I should have stayed in politics. But what I saw just horrified me. These people… In their desire to get a majority, the rules are bent, the laws broken, institutions are destroyed. The effects are there for anyone to see. You saw the roads: they’re intolerable. Twenty years ago the journey here used to take an hour; now it takes twice that. Electricity is now virtually non-existent, or at best very erratic. There is no healthcare, no education, nothing. Fifty years after independence there are still villages around here which have no drinking water. And now there are these hold-ups on the road. Because they are up to their neck in it, the police and the politicians turn a blind eye.”

“But isn’t that all the more reason for you to stay in politics?” I said. “If all the people with integrity were to resign, then of course the criminals will take over.”

“Today it is impossible to have integrity or honesty and to stay in politics in India,” replied Suleiman. “The process you have to go through is so ugly, so awful, it cannot leave you untouched. Its nature is such that it corrodes, that it eats up all that is most precious and vital in the spirit. It acts like acid on one’s integrity and sincerity. You quickly find yourself doing something totally immoral and you ask yourself: what next?

We fell silent for a few minutes, watching the sun setting over the sugar mill. Behind us, the bearer reappeared to announce that the rajah’s dal and rice was finally ready. It was now nearly five o’clock.

“In some places in India perhaps you can still achieve some good through politics,” said Suleiman. “But in Lucknow it’s like a black hole. One has an awful feeling that the forces of darkness are going to win here. It gets worse by the year, the month, the week. The criminals feel they can act with impunity: if they’re not actually members of the Legislative Assembly themselves, they’ll certainly have political connections. As long as they split 10% of their takings between the local M.L.A and the police they can get on and plunder the country without trouble.

“Everything is beginning to disintegrate,” said Suleiman, still looking down over the parapet. “Everything.”

He gestured out towards the darkening fields below. Night was drawing in now, and a cold wind was blowing in from the plains: “The entire economic and social structure of this area is collapsing,” he said. “Its like the end of the Moghul Empire. We’re regressing into a Dark Age.”

Credits : William Dalrymple

On the eve of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Lucknow, the capital of the Kingdom of Avadh, was indisputably the largest, most prosperous and most civilised pre-colonial city in India. Stories that have come to epitomise the fevered fantasies of whole generations of Orientalists seem for once not to have been too far. Many books and articles have been dedicated to this muse in disguise called `Avadh’. Here William Dalrymple writes about the refinement that Awadh was all about. Should you need more readings on Lucknow or the kingdom of Avadh do mail us for recommendations.

This tour covers a heritage lane and explains the culture, people and lifestyle of Lucknow within just a span of 2 hrs. No heritage monuments are a part of this walk.

This tour covers a heritage lane and explains the culture, people and lifestyle of Lucknow within just a span of 2 hrs. No heritage monuments are a part of this walk. This is an exclusive special interest tour that operates every day, except Friday. Ideal time of starting would be 0800 hrs, though may be altered as per individual requirements, while expect to return to the hotel by 1700 / 1800 hrs.

This is an exclusive special interest tour that operates every day, except Friday. Ideal time of starting would be 0800 hrs, though may be altered as per individual requirements, while expect to return to the hotel by 1700 / 1800 hrs. Most enjoyable for British Travellers. Check schedule with us.

Most enjoyable for British Travellers. Check schedule with us. This tour covers Kaiserbagh, the erstwhile palace complex of Wajid Ali Shah, reconstructing it virtually and understanding the personality of the ruler. This walking tour ends at The Kotwara House over a cup of tea and cookies.

This tour covers Kaiserbagh, the erstwhile palace complex of Wajid Ali Shah, reconstructing it virtually and understanding the personality of the ruler. This walking tour ends at The Kotwara House over a cup of tea and cookies.

A 42-feet-long and 11-feet-long gondola (a traditional, flat-bottomed boat) has been unearthed by the officials of the Uttar Pradesh State Archaeological Department (UPSAD) while excavating the 220-year-old Chhatar Manzil of Lucknow. The Chattar Manzil once served as a palace for the begums (royal women) of Awadh.

A 42-feet-long and 11-feet-long gondola (a traditional, flat-bottomed boat) has been unearthed by the officials of the Uttar Pradesh State Archaeological Department (UPSAD) while excavating the 220-year-old Chhatar Manzil of Lucknow. The Chattar Manzil once served as a palace for the begums (royal women) of Awadh.

In the days when I was tramping around in the alleys of Lucknow trying to capture the ineffable essence of this multi-layered city, I was led to a small group of old and young courtesans in Gulbadan’s kotha near the

In the days when I was tramping around in the alleys of Lucknow trying to capture the ineffable essence of this multi-layered city, I was led to a small group of old and young courtesans in Gulbadan’s kotha near the

(Pic: Gilbert Wheeler Cole – Superintendent of Police, Fatehgarh – Killed in action on 3rd April 1936)

(Pic: Gilbert Wheeler Cole – Superintendent of Police, Fatehgarh – Killed in action on 3rd April 1936)

To my amazement the memorial looked cleaner than it had in the 1990’s pictures. It also had a new wall surrounding it and a square of trees. Apparently, the new Superintendent of police had ordered the restoration work when he had been appointed to the district earlier in the year and they had had a parade on 22nd October to commemorate martyr’s day. I laid a garland of flowers at the base of the memorial and took numerous photos, including some with the police officers who were showing me around. I did mention that somehow over the years my grandfather’s name had been changed from Gilbert to Cilbert (easily done if you never see English Christian names).

To my amazement the memorial looked cleaner than it had in the 1990’s pictures. It also had a new wall surrounding it and a square of trees. Apparently, the new Superintendent of police had ordered the restoration work when he had been appointed to the district earlier in the year and they had had a parade on 22nd October to commemorate martyr’s day. I laid a garland of flowers at the base of the memorial and took numerous photos, including some with the police officers who were showing me around. I did mention that somehow over the years my grandfather’s name had been changed from Gilbert to Cilbert (easily done if you never see English Christian names).

As we started our search of the undergrowth a crowd of local children gathered and started the new Sunday afternoon game of “hunt the grave stone”. From the photos we managed to work out which quarter of the grounds the grave was, but we did not seem to be having much luck finding the correct inscription. I was just looking for Pankaj to ask him whether to ask whether there was a place where the broken tombstones were laid aside, when a cry went up from behind some bushes “Cole Sahib!”. After fighting my way through some bushes there it was!

As we started our search of the undergrowth a crowd of local children gathered and started the new Sunday afternoon game of “hunt the grave stone”. From the photos we managed to work out which quarter of the grounds the grave was, but we did not seem to be having much luck finding the correct inscription. I was just looking for Pankaj to ask him whether to ask whether there was a place where the broken tombstones were laid aside, when a cry went up from behind some bushes “Cole Sahib!”. After fighting my way through some bushes there it was!

So, two out of four missions accomplished, and it was still only about 4.30 in the afternoon. We headed back towards Farrukhabad to drop off the helpful local who had shown us where the graveyard was. As we were driving, I mentioned that one of the next two aims was to find out whether the bungalow my grandfather had lived in was still identifiable. To help us with this the local man suggested searching out the current Superintendent of Police’s (SP’s) bungalow. The only things we had to work with were a photo from the 1930’s and a reminiscence from my mother (or Grandmother?) that it had fantastic views across the Ganges. After many drives down dead end lanes that ended up at the top of a river cliff overlooking the flood plain of the river we came across the Superintendent’s Bungalow and enquired with the sentry whether he recognised anything from the photo. He sent for another policeman who invited us into his office and offered us some chai. After much discussion and searching for records, etc. I was told we were waiting to see whether the current SP had time to see us. Half an hour later we were led though a gate in a wall into the impressive front garden of the bungalow. Unfortunately, the porchway looked nothing like the one in the photo!

So, two out of four missions accomplished, and it was still only about 4.30 in the afternoon. We headed back towards Farrukhabad to drop off the helpful local who had shown us where the graveyard was. As we were driving, I mentioned that one of the next two aims was to find out whether the bungalow my grandfather had lived in was still identifiable. To help us with this the local man suggested searching out the current Superintendent of Police’s (SP’s) bungalow. The only things we had to work with were a photo from the 1930’s and a reminiscence from my mother (or Grandmother?) that it had fantastic views across the Ganges. After many drives down dead end lanes that ended up at the top of a river cliff overlooking the flood plain of the river we came across the Superintendent’s Bungalow and enquired with the sentry whether he recognised anything from the photo. He sent for another policeman who invited us into his office and offered us some chai. After much discussion and searching for records, etc. I was told we were waiting to see whether the current SP had time to see us. Half an hour later we were led though a gate in a wall into the impressive front garden of the bungalow. Unfortunately, the porchway looked nothing like the one in the photo!

We were then invited into a living room where we were offered another cup of chai (superior china this time!), sweets and savouries. After a few minutes SP Santosh Kumar Mishra came out, set up his phone and police radio, and I explained what we had already found and what I was looking for. SP Mishra spoke perfect English as apparently, he had worked abroad for several years as an engineer before coming home to India to serve his people as a policeman. At 36 he was only a few years older than my grandfather, when he held the same post.

We were then invited into a living room where we were offered another cup of chai (superior china this time!), sweets and savouries. After a few minutes SP Santosh Kumar Mishra came out, set up his phone and police radio, and I explained what we had already found and what I was looking for. SP Mishra spoke perfect English as apparently, he had worked abroad for several years as an engineer before coming home to India to serve his people as a policeman. At 36 he was only a few years older than my grandfather, when he held the same post.

After a few minutes we turned down a side road, like some of the one’s we had already investigated, and stopped in front of an old brick wall with what looked like bricked up archways. Some of the officers who had been in the area for a long time believed that this was all that remained of the 1930’s bungalow, which had been on a far larger plot of land that may have stretched as far as the current SP’s bungalow. The land had progressively been sold off by the government because of its prime location next to the Ganges. After a brief look around, I was driven back in the convoy to the SP’s bungalow where we agreed some plans for the next day. By this time, it was around 7 pm so we drove back to the hotel and I had dinner in the hotel restaurant (only vegetarian food was available, and no beer could be consumed at the tables).

After a few minutes we turned down a side road, like some of the one’s we had already investigated, and stopped in front of an old brick wall with what looked like bricked up archways. Some of the officers who had been in the area for a long time believed that this was all that remained of the 1930’s bungalow, which had been on a far larger plot of land that may have stretched as far as the current SP’s bungalow. The land had progressively been sold off by the government because of its prime location next to the Ganges. After a brief look around, I was driven back in the convoy to the SP’s bungalow where we agreed some plans for the next day. By this time, it was around 7 pm so we drove back to the hotel and I had dinner in the hotel restaurant (only vegetarian food was available, and no beer could be consumed at the tables).

Next morning after breakfast we left the hotel at 9 am on a quest to find a plaque in the village of Pipar Gaon, which was where the incident occurred in April, 1936. Pankaj had arranged with the Superintendent of Police the previous evening that we would be shown the spot by officers from the local police station, so we first drove to the village of Mohammadabad. After further chai and a search through an old record book, to see whether they could find a record of the incident we headed off in convoy back towards the village of Pipar Gaon.

Next morning after breakfast we left the hotel at 9 am on a quest to find a plaque in the village of Pipar Gaon, which was where the incident occurred in April, 1936. Pankaj had arranged with the Superintendent of Police the previous evening that we would be shown the spot by officers from the local police station, so we first drove to the village of Mohammadabad. After further chai and a search through an old record book, to see whether they could find a record of the incident we headed off in convoy back towards the village of Pipar Gaon.

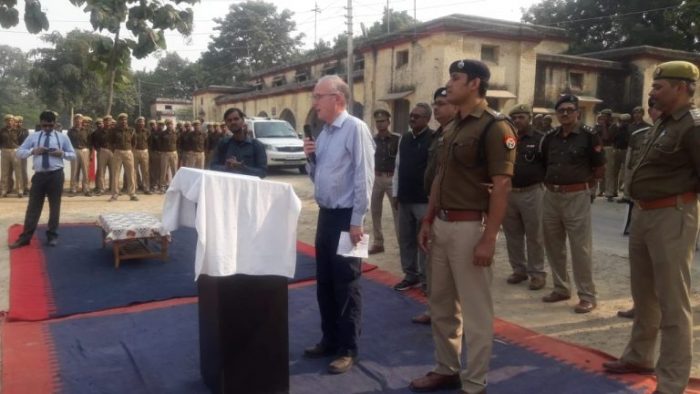

Within a few minutes quite a crowd had gathered, which included various members of the local press. Of course, this resulted in a long photo session along with various selfies with any of the locals who possessed a camera phone. The police officers then joined in the lesson of the day at the school, which happened to be about road safety and traffic rules! I was asked to say a few words to the children about the reason I was there.

Within a few minutes quite a crowd had gathered, which included various members of the local press. Of course, this resulted in a long photo session along with various selfies with any of the locals who possessed a camera phone. The police officers then joined in the lesson of the day at the school, which happened to be about road safety and traffic rules! I was asked to say a few words to the children about the reason I was there. Soon after midday we arrived back at the police lines, which appeared to be far busier than the previous day with uniformed officers all over the place. We were ushered into the armoury building and asked to wait on the veranda (and served another cup of chai).

Soon after midday we arrived back at the police lines, which appeared to be far busier than the previous day with uniformed officers all over the place. We were ushered into the armoury building and asked to wait on the veranda (and served another cup of chai).  After fifteen minutes or so we were escorted across to another building, greeted by various senior police officers and shown into an audience room where I was sat at a place of importance next to the large desk. A few minutes later SP Mishra arrived with various officers and proceeded to check that all his communication was functioning. There then followed a session that I doubt would relate to anything that goes on in a British police station. A series of petitioners came into the room, singularly and in groups; presented pieces of paper to the SP, which were written on and placed ready to file. There followed various prolonged discussions, in Hindi, which seemed to consist of arguments from the civilians followed by a proclamation from the SP or one of the other police officers. It was difficult to follow exactly what was happening as I only occasionally got translations. Apparently one case was a land dispute; another the resulting property dispute after a married daughter had decided to move to a city after her marriage rather than live in the parental home and another something to do with a suicide. The final case seemed more like British police matter as three men came in looking as though they had been in a fight. I commented that most of the issues we heard in that short session would probably be resolved in other ways in England, often involving the expense of consulting a lawyer, at far greater expense to the plaintiff. Of course, some would not occur in the first place due to the difference in cultures. This system was the same in the days of the British Raj, so my Grandfather was probably involved with daily sessions like this although the population of the district was probably a lot lower than the current two million.

After fifteen minutes or so we were escorted across to another building, greeted by various senior police officers and shown into an audience room where I was sat at a place of importance next to the large desk. A few minutes later SP Mishra arrived with various officers and proceeded to check that all his communication was functioning. There then followed a session that I doubt would relate to anything that goes on in a British police station. A series of petitioners came into the room, singularly and in groups; presented pieces of paper to the SP, which were written on and placed ready to file. There followed various prolonged discussions, in Hindi, which seemed to consist of arguments from the civilians followed by a proclamation from the SP or one of the other police officers. It was difficult to follow exactly what was happening as I only occasionally got translations. Apparently one case was a land dispute; another the resulting property dispute after a married daughter had decided to move to a city after her marriage rather than live in the parental home and another something to do with a suicide. The final case seemed more like British police matter as three men came in looking as though they had been in a fight. I commented that most of the issues we heard in that short session would probably be resolved in other ways in England, often involving the expense of consulting a lawyer, at far greater expense to the plaintiff. Of course, some would not occur in the first place due to the difference in cultures. This system was the same in the days of the British Raj, so my Grandfather was probably involved with daily sessions like this although the population of the district was probably a lot lower than the current two million.

After this session was over, we strolled down to the parade ground with an entourage of people. We were met there by a couple of hundred police recruits, lined up in military style ranks, who were called to attention and saluted as the SP arrived. I was then shown into the veranda of the old hospital building, which overlooks the monument, and asked to show the waiting press corps some of the pictures and documents I had shown SP Mishra the evening before. They all took notes, and some tried taking TV videos of my tiny tablet screen. This was to try to explain to them what was about to happen and why the commemoration was more about the dedication of policeman in the past, and into the future, rather than a throw-back to the days of empire.

After this session was over, we strolled down to the parade ground with an entourage of people. We were met there by a couple of hundred police recruits, lined up in military style ranks, who were called to attention and saluted as the SP arrived. I was then shown into the veranda of the old hospital building, which overlooks the monument, and asked to show the waiting press corps some of the pictures and documents I had shown SP Mishra the evening before. They all took notes, and some tried taking TV videos of my tiny tablet screen. This was to try to explain to them what was about to happen and why the commemoration was more about the dedication of policeman in the past, and into the future, rather than a throw-back to the days of empire.

Next, we paraded into the enclosure around the monument where I was given a wreath to place on the steps (the inscription had meanwhile been changed to Gilbert). I am sure I should have had a suit with me rather than the clothes I had been travelling with for the last two weeks. I am not used to being in the middle of a paparazzi pack!

Next, we paraded into the enclosure around the monument where I was given a wreath to place on the steps (the inscription had meanwhile been changed to Gilbert). I am sure I should have had a suit with me rather than the clothes I had been travelling with for the last two weeks. I am not used to being in the middle of a paparazzi pack!

As we were leaving the parade ground SP Mishra asked me whether I knew anything about military drill. As I said the only experience, I had was with the scouts he asked the RI to give a quick drill demonstration to us. I managed to capture the whole of this on video on my phone.

As we were leaving the parade ground SP Mishra asked me whether I knew anything about military drill. As I said the only experience, I had was with the scouts he asked the RI to give a quick drill demonstration to us. I managed to capture the whole of this on video on my phone.

Once this wrapped up, we walked back to the SP’s audience room where I shook hands with the local BJP MP who received his own explanation of the events of the day. SP Mishra then presented me with a book as a memento of the occasion. By this time, it was 3.30 pm and we had at least a 3-hour journey back to Lucknow to get some sleep before my early morning flight back to London. We therefore made our apologies and headed off. Unfortunately, we got a little lost on the way out of Fatehgarh but, thanks to the expressway, we got back to Lucknow soon after 7pm.

Once this wrapped up, we walked back to the SP’s audience room where I shook hands with the local BJP MP who received his own explanation of the events of the day. SP Mishra then presented me with a book as a memento of the occasion. By this time, it was 3.30 pm and we had at least a 3-hour journey back to Lucknow to get some sleep before my early morning flight back to London. We therefore made our apologies and headed off. Unfortunately, we got a little lost on the way out of Fatehgarh but, thanks to the expressway, we got back to Lucknow soon after 7pm.

Well you don’t get that sort of treatment of your average Explore group tour to India! Thanks, must go to the Farrukhabad/Fatehgarh police force and especially SP Santosh Kumar Mishra for making me so welcome in their district. I would also like to thank my guide Pankaj Singh and driver Thapa from Tornos for looking after me so well over the last four days. All four target sights visited and a lot more besides!

Well you don’t get that sort of treatment of your average Explore group tour to India! Thanks, must go to the Farrukhabad/Fatehgarh police force and especially SP Santosh Kumar Mishra for making me so welcome in their district. I would also like to thank my guide Pankaj Singh and driver Thapa from Tornos for looking after me so well over the last four days. All four target sights visited and a lot more besides!