Volume: 8, No: 01 ; January-2014

For modern India, the defining moment is the country’s independence and partition. The ideology that ultimately led to India’s division stemmed from the uncertainty and apprehension experienced by Indian Muslims after the deposition of Bahadur Shah Zafar. While that event had instilled a deep sense of deprivation in Muslims, there was also a gradual decline in their social and economic conditions after 1857. Realising that many of the ills stemmed from their own social, religious and intellectual stasis, Muslim intellectuals and reformers encouraged the spread of modern education among Muslims. As they introduced progressive ideas through their writings, they met with resistance from the conservatives who lashed out against western education as un-Islamic. This led to a confrontation between the traditionalists and the advocates of modern ideas. Consequently, during the early decades of the last century, the entire Muslim community was politically, socially, intellectually, and religiously in ferment.

Attia Hosain was born in such a world of deep conflicts and intense debates in 1913. Her family subscribed to progressive ideas. While her father had studied at Cambridge University, her mother had established an institute for women’s education and welfare in Lucknow, her hometown. She was educated at Lucknow’s Isabella Thoburn College a women’s college affiliated to the University of Lucknow. At home she was also taught Arabic and Persian. It was the time when the need for education among Muslim women was a contentious issue. A reformer like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan was emphasising its necessity in his writings. Urdu writer and reformer Nazir Ahmad Dehlvi (1830 – 1912) had written “Bina-tul-Nash”, a novel advocating women’s education. In Lucknow, many organisations and women’s magazines were raising awareness on the issue.

The Lucknow of the 1920s and ’30s was politically and intellectually volatile. Liberal humanism, Marxism, and progressive ideas about women’s emancipation and social equality contended with the traditionalist, conservative, and anti-western ideas. Attia began writing for newspapers The Pioneer (Calcutta) and The Statesman (Calcutta). In 1932, an event of far reaching cultural and intellectual consequences was the publication of “Angaray”, a collection of short stories and a play by Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmed Ali, Rashid Jahan and Mahmuduzzafar. The four young Muslim intellectuals from Lucknow introduced western ideas and castigated the contemporary Muslim society. These radical voices exerted their influence on the young Attia. Despite her aristocratic background, she was able to see the hypocrisies and contradictions of her class and social milieu.

Her sensitive mind had made her restless about the feudal aristocracy, the firmly entrenched social stratification, the illiteracy and poverty, and the repression of Muslim women. For a young woman of her sensibility, it was impossible not to be influenced by the Leftist and nationalist ideas, whose hotbed Lucknow was now turning out to be. Her brother had leftist leanings and associated with stalwarts like Ahmed Ali, Mulk Raj Anand and Sajjad Zaheer. Hosain also attended the 1936 Lucknow session of Association chaired by Premchand.

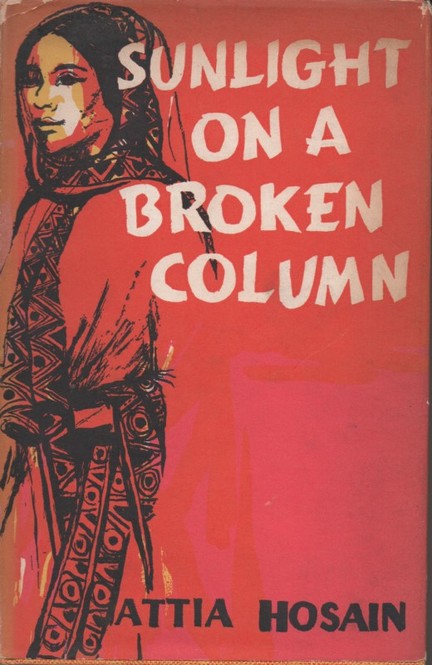

She had begun writing short stories from a very young age. She published her first collection of short stories titled “Phoenix Fled” in 1953. Her only novel, “Sunlight on a Broken Column”, was published in 1961. However, the manuscript of an unfinished novel was discovered among her papers after her death in 1998. It was recently published as “No New Lands, No New Seas”, along with some of her uncollected stories in “Distant Traveller: New and Selected Fiction”.

Among her stories, “Storm” can be considered a representative work, characterised by stylistic simplicity and satire. Hosain portrays here characters who are vain and superficial, no doubt drawn from the world around her. When an unknown woman takes refuge from a storm in the house of an ‘upper class’ family, the snobbish attitude of the women becomes obvious. The daughter of the family, a young girl, helps the woman and offers her an umbrella so that she can go out without getting drenched. She meets this woman many times again, but when the family finds out she is prohibited from seeing her again. The hypocrisy of the privileged bureaucratic class is well brought out.

Her short story “Phoenix Fled” is famous for its ending. The protagonist, an old woman, is unwilling to leave her ancestral house to go to another country born after partition. Her family abandons her and departs. As a mob gathers to burn down her house, she expresses her sole concern as follows:

“Mind,” she scolded, pointing her bony figure, “mind you do not step on the doll’s house.”

Though tinged with sentimentality, the pathos of the ending has been compared with that of some stories of Katherine Mansfield, whose influence is obvious in Hosain’s stories. Her stories are characterised by realistic and vivid details, influenced no doubt by the social realism of the progressive writers.

Encouraged by the poet laureate C.S. Lewis, Hosain wrote her novel in England. The story is narrated by the fourteen-year-old Laila, who, very much like the aspiring writer in “Storm”, exposes the hollowness, pretensions, and hypocrisies of the world she inhabits. Retaining the ability to look at her class and family with unprejudiced eyes, she captures a culture in flux with its paradoxes and contradictions. “Sunlight on a Broken Column” depicts the Muslim society of the first half of the 20th Century; Laila’s desire to be well educated like her male counterparts is opposed by her family. The irony of her world is that Zahara, an upper class girl, is married against her will. In stark contrast, Nandi, the servant girl, is able to marry as she desires.

Indeed, Hosain describes a society in which religion and faith were not yet divisive but provided a richness and variety to its culture with their distinct festivals, rituals and beliefs. She never quite came to terms with the fact that a society where different religions and cultures thrived side by side could suddenly be rent apart. The pain and the sadness infuse her writing without bitterness or rancour.

When she visited her family house five years after Partition, she discovered that it “had buried one way of life and accepted another.” She later wrote : “In its decay, I saw all the years of our lives as a family; the slow years that had evolved a way of life, the short years that had ended it.” “Sunlight…” had its origin in that moment. Its title drawn from T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men”, the novel, as she wrote, was meant to be her elegy to “the breaking up of a family, when the whole background (was) changing.” Broken columns symbolise the ruins which her hometown’s thriving culture had suddenly turned into. That culture was a way of life which, despite its flaws, had pleasures to offer, not the least among them being the illusion of a stable world.

Hosain is, however, at her evocative best in “Sunlight…”, written with the intention to capture a phase and a world fast disappearing, and only existing in her memory. Like Ahmed Ali in “Twilight in Delhi”, she writes as a chronicler and a documenter.

“Sunlight on a Broken Column” should certainly be considered as a definitive work that describes the crumbling feudal order and the undercurrents, political and cultural, which eventually led to India’s partition. To confine it, however, to just that reading would be unjust, for the novel is meant to transcend the topical and the political. The author revealed she chose to write it because of a feeling that the “other world that (she) actually lived in” was fading into oblivion and an inner urge to acknowledge and preserve for posterity that “there were people then who believed in the future.”

It is this faith in human life and future that informs her vision and confirms Attia Hosain as a writer in the humanist tradition.

Credits : THE HINDU – 31st October 2013, Written by Prof Shikoh Mohsin Mirza

LUCKNOWLEDGE is an initiative by Tornos. We do not intend to intrude your privacy and thus have an automated UNSUBSCRIBE system. At any point you may unsubscribe to our e-column or subscribe to it again through a link on our website. The above article is shared and in no way intends to violate any copy right or intellectual rights that always remains with the writer/publisher. This e-column is a platform to share an article/event/update with the netizens and educate them about Destination Lucknow.